Everyday Things I Love Here

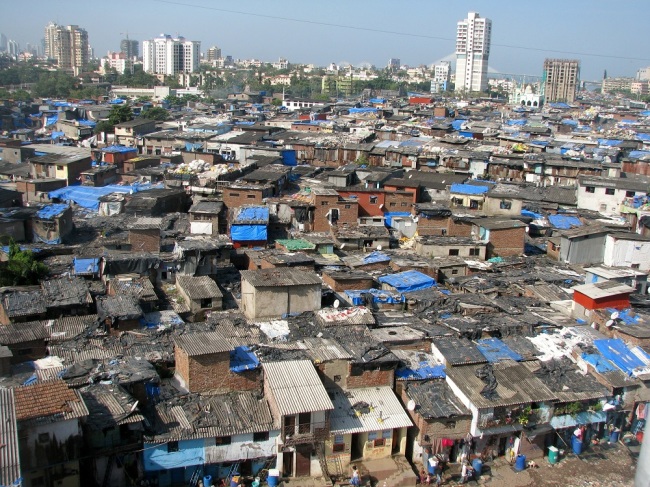

The world’s fourth largest consumer of energy in absolute terms, India doesn’t even make the list of top 150 nations for per capita electricity consumption (According to Index Mundi, India ranks 153rd in the world with a per capita consumption of 498.39 kWh. The US, by comparison, ranks 9th with 11,919.8 kWh per capita consumption). With approximately 1.4 billion of the world’s 7 billion people living here in India, it is only logical that the nation will consume a large chunk of energy. However, a great deal of India’s low per capita energy consumption can be explained by a large number of people living without electricity or running water. In the future, if the number of Indians with access to electricity increases, energy consumption in absolute terms will also increase. (An interesting debate is present here: If it is good for people to have access to electricity and running water and we believe they should have access to these resources, doesn’t access to these resources paradoxically introduce pollution and energy consumption that is viewed negatively? If India increases quality of life for rural areas currently living without electricity, they will in reality become bigger energy consumers and bigger polluters. Is this desirable? I think so, but this topic could be debated)

Those in India fortunate enough to have access to resources such as electricity and water take many steps to conserve them. Wasting resources in general is much less common in India than I am accustomed to in the United States. In India energy, water, and food are consumed cautiously and with much more attention than is given in the US, where the provision of each of these resources is often taken for granted. Water and electricity supplies are extremely volatile here, especially for rural areas. For example, for the first time in seven years Pune had a monsoon good enough to completely fill the water reservoirs. Good rains- and therefore water access- are not a guarantee in India.

How does India respond to these challenges in resource management? Brilliantly, I think. Here are five ways Indians conserve resources through simple lifestyle choices. Maybe you can consider using some of these in your homes! I know I will.

Power Outlet Switches

Fascinating to me at first, power outlets that switch energy flow to individual electric sockets on and off are obvious solutions to energy conservation. Why do we need a constant flow of energy to sockets that aren’t powering anything? In our house, we take care to switch off power outlets when we aren’t using them and to only switch them on until our appliances are fully charged, instead of allowing them to keep consuming energy after the batteries are fully recharged. Equal care is taken to ensure that lights and fans are switched off as soon as we leave the room. While switching off lights and fans was a rule in my house growing up, we didn’t even have the capability to switch off power outlets. I think it’s wonderful that it’s standard in India to conserve energy through simple switches on outlets. Even though outlets in the US may not be absorbing a great deal of energy if nothing is plugged in, think of all the appliances we leave running (televisions, lights, fans) without thinking about the energy that’s being consumed? Switches are a physical reminder to be conscious of energy flows. Here’s a picture of one of the power outlets in my home:

Air Drying Clothing

If you look at the picture below, you might understand my hesitation the when my host mom asked me to hang my clothes on the drying rack during my first week here. If you can’t tell from the photo, let me just inform you that the drying rack she asked me to use is suspended at about ten feet in the air. How am I supposed to hang my clothes on a rack I couldn’t even reach? I asked her. After a dose of teasing me about not knowing how to hang clothes, Aai showed me how to roll pants a few times from the waist, place the pants on the tip of a bamboo stick, and using the stick drape the pants over the drying rack so that air can reach the fabric. After watching Aai repeat this process a few times I felt confident that this would be easy. After all, she was draping those clothes like it was a piece of cake…I was wrong! I am now two months into the program and just now figuring out how to hang clothes without dropping them, hitting myself in the head with the bamboo stick, or getting the clothes stuck in awkward wads on the drying rack and having to reposition them a few times before successfully draping them across the pole. Whew! Jokes aside, the fact that Aai’s drying rack is a permanent fixture in her porch shows how commonplace air drying clothes is in India. In a warm and breezy climate, why waste energy on a drying machine when nature will do the same job for you? In fact, Aai doesn’t even own a drying machine. I love this! I love living in a home that doesn’t waste energy for the convenience of 90 minute drying cycles and the scent of dryer sheets. Are these conveniences really worth it when drying machines are typically the second-highest energy consuming appliances in households?

A photo diary of my air drying struggles is provided for your entertainment below:

Once our clothes come out of the wash, they are wrung out and placed in buckets

We are then given the task of hanging our clothes on the three clothing lines pictured above

…with this bamboo stick.

First, place the clothes on the tip of the bamboo stick…

Second, slowly raise the stick towards the poles, taking care not to drop the newly cleaned clothes

Third, gently toss the clothes over the drying line and spread them so the air reaches them evenly. Repeat!

Bucket Showers

While some of you may be ready to jump on the bandwagon of using power outlet switches and air drying your clothes, I’ll be the first to admit that bucket showers are a slightly less quixotic proposition. Bucket showers are at first…awkward. Wait…where’s the shower head? Okay, so there is no shower head…Then how am I supposed to rinse out shampoo suds? How do I get my hair and body wet without just dunking my head (and limbs) in the bucket? How is one bucket of water enough to replace the fifteen minute steady-water shower I take at home? I was definitely a bucket shower noob when I came abroad. With a little practice, though, I’ve learned that bucket showers are surprisingly efficient! (A, because they save water and B, because they’re less enjoyable than American showers so I waste less time in the shower ;))

Here’s a simple 101 guide to bucket showering for those of you looking to save the planet or live abroad (Pictures of buckets below for your convenience):

- Position large bucket below water spout

- Turn on water (read my spiel on hot water below. Spoiler alert: hot water not guaranteed)

- If the position of the spout permits, duck your head underneath the spout in order to wet your hair while still catching water in the bucket; shampoo hair while waiting for the bucket to fill

- Once the large bucket is filled, use the smaller bucket to rinse out the suds in your hair. This will take about three or four small buckets; half of your water should be remaining after this step

- Since your body is wet from rinsing out the shampoo, condition your hair and then take advantage of this moment to thoroughly scrub your body

- Use the remaining water to rinse out the conditioner; this will also result in rinsing the majority of soap off of your body. Use last bit of water in bucket to rinse off remaining suds

Hot Water Heaters

As I hinted at above, hot water in India is not a given. One of the first conversations I had with my host mom involved her asking me if I take hot or cold showers. While this would be an obvious answer in the US, not everyone here has the luxury of warm showers. Luckily, my home has a hot water boiler that is used for taking showers. 5-10 minutes before I plan on showering I flip on the geyser, which turns on the water boiler and heats the water tank for my shower. I then fill the bucket with water (Steps 1-3 above) and flip off the geyser switch to minimize energy used heating the water. Rather than using energy to keep water hot all the time- even when we’re not using it- Indians wait five minutes for the water to heat up and save loads of energy. Isn’t this something we should be trying at home? Here’s a photo of our geyser switch (the one with the red button):

Cook Only How Much You Will Eat

I loved leftovers growing up (Mom and Dad, I miss your cooking!), but for many of my friends growing up, having leftovers for dinner was less than desirable. These people would be thrilled to know that in India the concept of leftovers is extremely different! In our house, Aai only makes enough food for each of us to be full and (ideally) no excess food remains at the end of a meal. While in my family we would always package and refrigerate food we didn’t finish for dinner, this unfortunately didn’t guarantee that the food would be eaten at a later time. Too often in the United States, whether it be in homes or at restaurants or other public venues, food is made in excess and easily thrown out or packaged away and forgotten on the back of a refrigerator shelf. Reducing how much we make for a meal could be a great first step in eliminating food waste at home! I will definitely try to master the art of perfectly portioned meals that Aai so easily cooks every night once I am home.